While almost everyone favours conservation of plants and animals around the globe, it is far from clear how this broad goal can be disarticulated into smaller issues. Once we have done this the solution of the conservation problem should be simple. But it is not (Sutherland et al, 2021). Take an example of the koala in Australia, cute mid-size marsupials that live in trees and eat leaves. If koalas are to be protected, you must protect forests, but if you protect forests the companies that survive by logging on both private and crown land will be adversely affected. We have an immediate conflict, so how do we decide what to do. One response which we can label have-your-cake-and-eat-it-too suggests that we use some of our forests for logging and protect some forests for ecological reserves. Everyone is now happy, but things unravel. As the human population grows, we need more wood, so over time we would have to log more and more of the forested areas that could support koalas. Conflict now, jobs for loggers vs. conservation of koalas. The simplest solution is to decide all this in economic terms. Logging produces much money; conservation is largely a drain on the taxpayers. To propose that conservation should win, ecologists will pull out David Attenborough to show all the beauties of the forest and to point out that the forest contains many other animals and plants and not just trees for lumber. Stalemate, and social and economic goals begin to override the ecological issue until some compromise is suggested and accepted.

While this kind of oversimplified scenario is common, the whole issue of conservation decision making is fraught with problems and who is going to decide these issues (Christie et al. 2022)? In a democracy in the good old days, you took a vote or a poll and decided to win/lose at >50% of the vote. But this cannot work for critical problems. We have a good example of this problem now with Covid vaccination requirements, and a vocal minority opposed to vaccinations. This now spills over into the issue of whether to wear a face mask or not. In all these kinds of scenarios science delivers a simple decision about the consequences of decision A vs decision B, but the problem is that society can refuse to recognize the scientific results or just prefer decision B with little visible justification. Science is not always perfect, adding further complications. And in the case of the covid virus, the virus can mutate in unexpected ways, complicating prognoses. In the case of protected conservation areas, we can suffer fires, floods, insect outbreaks and any number of events that affect the balance of decision making.

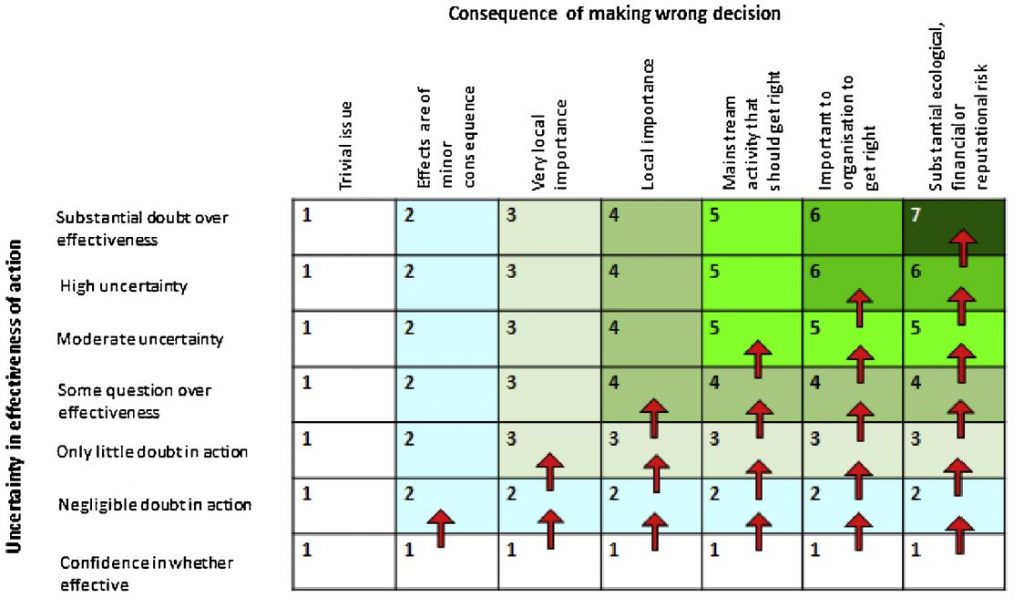

There is a large literature on decision making in conservation (e.g., Bower et al. 2018) and even good advice from the field of psychology about this problem of making decisions (Papworth 2017). The best systematic decision tree I have found is that in Sutherland et al. 2021). Sutherland et al. (2021) compiled a framework that can be used profitably in deciding on the level of evidence assessment (see Table 1 and Figure 1 below from their paper).

Table 1 and Figure 1 from Sutherland et al. (2021)

The Strategic Evidence Assessment Framework. Seven levels of evidence assessment, how to apply them.

| Assessment Level | Approach Used | General Database Application | Approximate Time to reflect on the evidence |

| 1 | No consideration of evidence | Continue with existing practice or make decisions without considering scientific evidence | none |

| 2 | Assertion but no independent consideration of evidence | Consultation with others (including experts) that affect decision but are not verified e.g. “we normally do this”, “accepted best practice is to do this” | minutes |

| 3 | Papers reviewed, looking at: | Read the title and/or summary points to determine whether action described in the paper is likely to be effective or not. Review effectiveness category e.g. “likely to be beneficial” on action page to decide whether action is likely to be effective or not | minutes |

| 4 | Read abstract to assess the evidence described in the paper in relation to the local problem | Tens of minutes- hours | |

| 5 | Read abstract, key results and conclusion assessing each paper in relation to the decision being made | Hours | |

| 6 | Read the full underlying paper/s. This is likely to affect decisions on study quality, relevance and modifications | Hours to days | |

| 7 | Comprehensive assessment | A systematic review of all available literature. Assessed papers summarised as part of new review | Months to a year |

Figure 1. A framework for considering the appropriate level of effort in decision making. Numbers refer to assessment level (Table 1). For a given decision about an action identify the column with the relevant level of consequence, start at the lowest level (1) and decide whether it would benefit from examining higher levels of evidence. Keep moving up until either the uncertainty in the effectiveness of the action is resolved from examining the evidence (from any platform) or the arrows end. This final number is the level at which the evidence assessment should occur. (From Sutherland et al. 2021 with permission).

Clearly conservation ecologists cannot use the highest assessment level for all issues that arise and must result to triage in many cases (Hayward and Castley 2018). But triage and assessment levels 1 and 2 should be rare in making judgement on what program to adopt. We need to get the science right for all conservation problems.

But this is not enough to get thoughtful political decisions. Some native species can be pests, yet nothing is done to reduce their damage (e.g. horses in North America and Australia, camels and goats in Australia, feral pigs in North America) and the list goes on. Nothing is done because of budget limitations or political concerns about “cute species”. The science of conservation is difficult enough, the social science of conservation is too often out of our control.

Bower, S.D., Brownscombe, J.W., Birnie-Gauvin, K. Ford, M.I. et al. (2018). Making Tough Choices: Picking the appropriate conservation decision-making tool. Conservation Letters 11, e12418. doi: 10.1111/conl.12418.

Christie, A.P., Downey, H., Bretagnolle, V., Brick, C., Bulman, C.R., et al. (2022). Principles for the production of evidence-based guidance for conservation actions. Conservation Science and Practice 4, e579. doi: 10.1111/csp2.12663.

Hayward, M.W. and Castley, J.G. (2018). Triage in Conservation. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 5, 168. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2017.00168.

Papworth, Sarah (2017). Decision-making psychology can bolster conservation. Nature Ecology & Evolution 1, 1217-1218. doi: 10.1038/s41559-017-0281-9.

Sutherland, W.J., Downey, H., Frick, W.F., Tinsley-Marshall, P., and McPherson, T. (2021). Planning practical evidence-based decision making in conservation within time constraints: the Strategic Evidence Assessment Framework. Journal for Nature Conservation 60, 125975. doi: 10.1016/j.jnc.2021.125975.