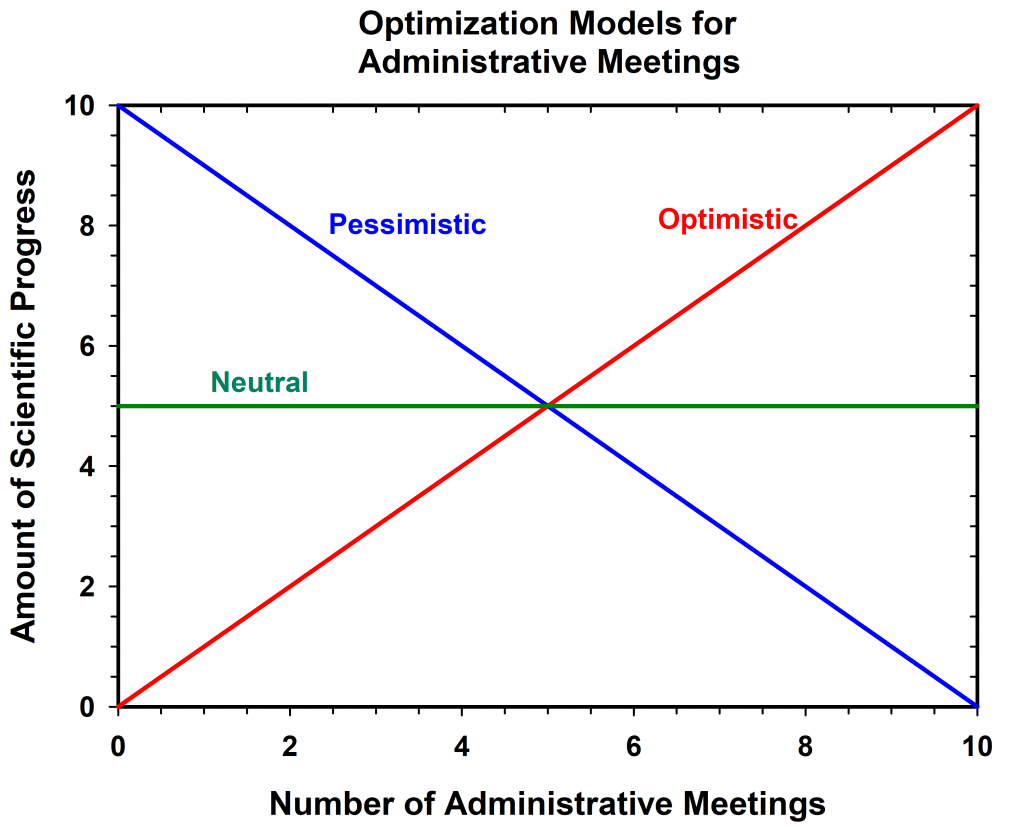

After talking and listening to my colleagues and friends who are still employed, I have the urge to try to quantify the utility of administrative meetings to scientific progress. I begin with a very simple model of what this relationship might look like.

The Neutral Model suggests that scientific progress is independent from the number of meetings that are focused on the scientific problem at hand. This is most likely the preferred model of administrators. The Optimistic Model suggests that scientific progress is positively related to the number of administrative meetings, possibly because the coordination among the members of the scientific team is enhanced. The Pessimistic Model suggests that the reverse is true, and if you as a scientific director wish to slow the progress of your scientific team, you should schedule many meetings all the time, presumably with a long agenda.

It is far from clear which model is appropriate for an ecological scientific team and more research is needed on this topic. Many scientists struggling with measurements and data collection are possibly attracted to the Pessimistic Model because time is the limiting element in their lives and both data and results are what limit progress. On the other hand, scientific administrators are possibly drawn to the Optimistic Model if they believe that meetings are the most important point of scientific progress and time is not the limiting factor, or perhaps they are drawn to the Neutral Model if they assume their scientists will work diligently and achieve the same goals no matter how many meetings are scheduled.

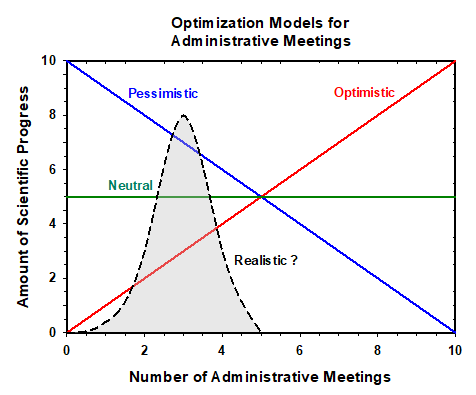

I hesitate to present this model given that the underlying mathematics are relatively simple, plus there are probably more business textbooks that make a detailed analysis of this issue than there are words in this blog. In a more realistic framework, we may have a peaked curve that indicate many meetings early in a project and fewer meetings once things are moving forward smoothly. There is going to be no magic numbers here, and the only purpose of this brief discussion is to think about how much you need to meet to define and deliver a set of objectives for a scientific question.

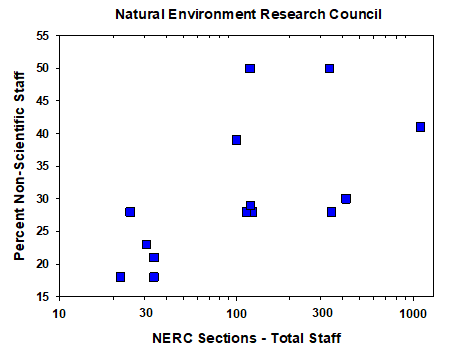

All my speculations above arose from an old paper (Moss 1978) illustrating these same general principles. Parkinson (1958) framed the law that “Work Expands To Fill The Time Available For Its Completion” and showed one consequence of this was that the fraction of administrators within a public organisation tends to increase irrespective of the amount of external scientific work done by that organisation. Moss (1978) produced these data to illustrate this law for British science data from 1976-77, illustrated in this graph:

Moss (1980) further elaborated on how Parkinson’s Law applied to scientific research organizations and noted that it may apply to many other research organizations. Although it is an old ‘law’ it may still be worth some discussion and consideration today.

Moss, R. (1978). An empirical test of Parkinson’s Law. Nature 273, 184. doi: 10.1038/273184a0.

Moss, R. (1980). Expanding on Parkinson’s Law. Nature 285, 9. doi: 10.1038/285009a0.