Now this is certainly a silly question. To be sure conservation ecologists collect much data, use rigorous statistical models, and do their best to achieve the general goal of protecting the Earth’s biodiversity, so clearly what they do must be the foundations of a science. But a look through some of the recent literature could give you second thoughts.

Consider for example – what are the hallmarks of science? Collecting data is one hallmark of science but is clearly not a distinguishing feature. Collecting data on the prices of breakfast cereals in several supermarkets may be useful for some purposes but it would not be confused with science. The newspapers are full of economic statistics about this and that and again no one would confuse that with science. We commonly remark that ‘this is a good scientific way to go about doing things” without thinking too much about what this means.

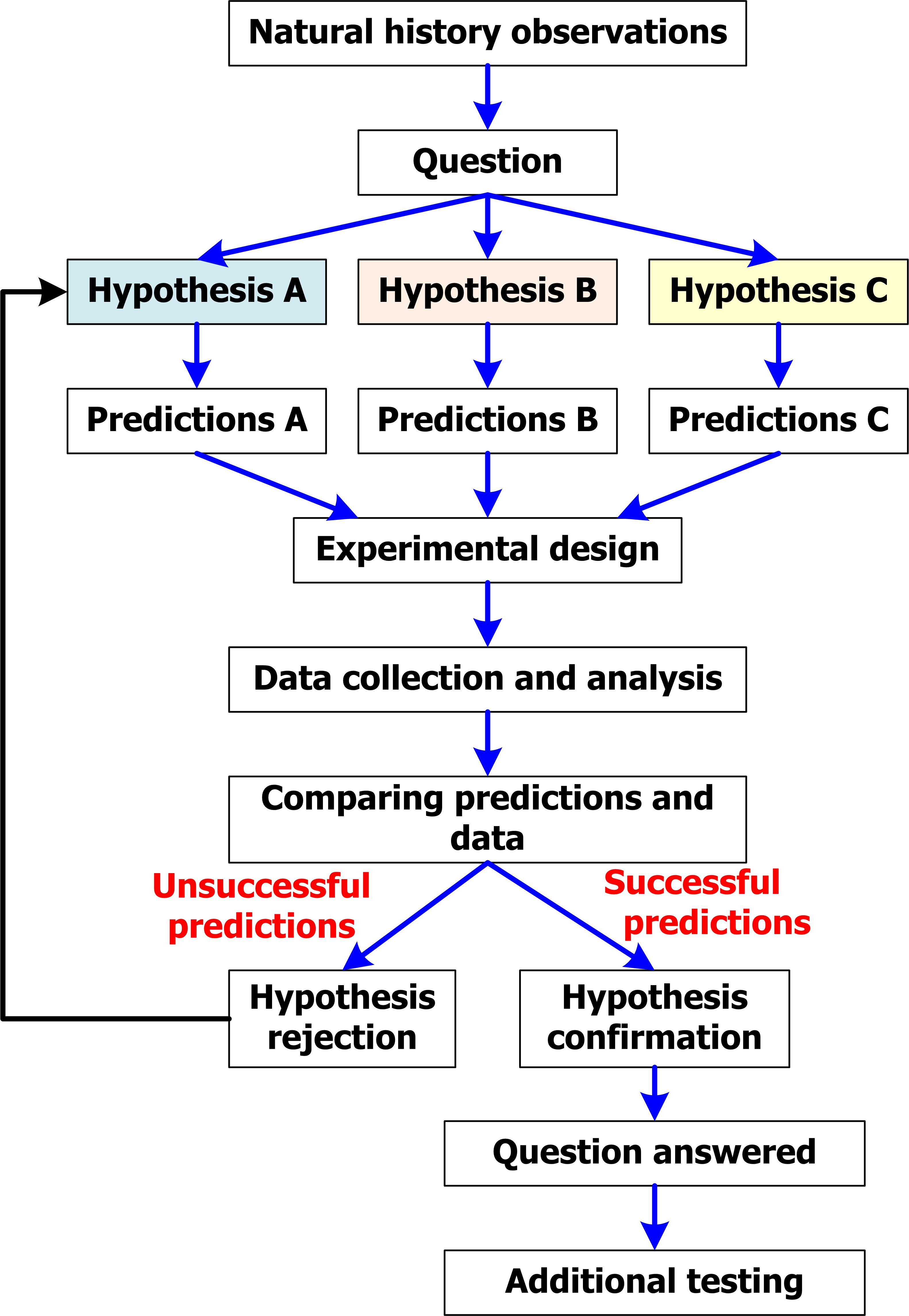

Back to basics. Science is a way of knowing, of accumulating knowledge to answer questions or problems in an independently verifiable way. Science deals with questions or problems that require some explanation, and the explanation is a hypothesis that needs to be tested. If the test is retrospective, the explanation may be useful for understanding the past. But science at its best is predictive about what will happen in the future, given a set of assumptions. And science always has alternative explanations or hypotheses in case the first one fails. So much everyone knows.

Conservation ecology is akin to history in having a great deal of information about the past but wishing to use that information to inform the future. In a certain sense it has a lot of the problems of history. History, according to many historians (Spinney 2012) is “just one damn thing after another”, so that there can be no science of history. But Turchin disagrees (2003, 2012) and claims that general laws can be recognized in history and general mathematical models developed. He predicts from these historical models that unrest will break out in the USA around 2020 as cycles of violence have broken out in the past every 30-50 years in this country (Spinney 2012). This is a testable prediction in a reasonable time frame.

If we look at the literature of conservation ecology and conservation genetics, we can find many observations of species declines, of geographical range shifts, and many predictions of general deterioration in the Earth’s biota. Virtually all of these predictions are not testable in any realistic time frame. We can extrapolate linear trends in population size to zero but there are so many assumptions that have to be incorporated to make these predictions, few would put money on them. For the most part the concern is rather to do something now to prevent these losses and that is very useful research. But since the major drivers of potential extinctions are habitat loss and climate change, two forces that conservation biologists have no direct control over, it is not at all clear how optimistic or pessimistic we should be when we see negative trends. Are we becoming biological historians?

There are unfortunately too few general ‘laws’ in conservation ecology to make specific predictions about the protection of biodiversity. Every one of the “ecological theory predicts…” statements I have seen in conservation papers refer to theory with so many exceptions that it ought not to be called theory at all. There are some certain predictions – if we eliminate all the habitat a species occupies, it will certainly go extinct. But exactly how much can we get rid of is an open question that there are no general rules about. “Protect genetic diversity” is another general rule of conservation biology, but the consequences of the loss of genetic diversity cannot be estimated except for controlled laboratory populations that bear little relationship to the real world.

The problems of conservation genetics are even more severe. I am amazed that conservation geneticists think they can decide what species are most ‘important’ for future evolution so that we should protect certain clades (Vane-Wright et al. 1991, Redding et al. 2014 and much additional literature). Again this is largely a guess based on so many assumptions that who knows what we would have chosen if we were in the time of the dinosaurs. The overarching problem of conservation biology is the temptation to play God. We should do this, we should do that. Who will be around to pick up the pieces when the assumptions are all wrong? Who should play God?

Redding, D.W., Mazel, F. & Mooers, A.Ø. (2014) Measuring evolutionary isolation for conservation. PLoS ONE, 9, e113490.

Spinney, L. (2012) History as science. Nature, 488, 24-26.

Turchin, P. (2003) Historical dynamics : why states rise and fall. Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey.

Turchin, P. (2012) Dynamics of political instability in the United States, 1780–2010. Journal of Peace Research, 49, 577-591.

Vane-Wright, R.I., Humphries, C.J. & Williams, P.H. (1991) What to protect?—Systematics and the agony of choice. Biological Conservation, 55, 235-254.