If ecology can team up with evolution to become a predictive science, we can all profit greatly since it will make us more like physics and the hard sciences. It is highly desirable to have a grand vision of accomplishing this, but there could be a few roadblocks on the way. A recent paper by Bay et al. (2018) illustrates some of the difficulties we face.

The yellow warbler (Setophaga petechia) has a broad breeding range across the United States and Canada, and could therefore be a good species to survey because it inhabits widely different climatic zones. Bay et al. (2018) identified genomic variation associated with climate across the breeding range of this migratory songbird, and concluded that populations requiring the greatest shifts in allele frequencies to keep pace with future climate change have experienced the largest population declines, suggesting that failure to adapt may have already negatively affected population abundance. This study by Bay et al. (2018) sampled 229 yellow warblers from 21 locations across North America, with an average of 10 birds per sample area (range n = 6 to 21). They examined 104,711 single-nucleotide polymorphisms. They correlated genetic structure to 19 climate variables and 3 vegetation indices, a measure of surface moisture, and average elevation. This is an important study claiming to support an important conclusion, and consequently it is also important to break it down into the three major assumptions on which it rests.

First, this study is a space for time analysis, a subject of much discussion already in plant ecology (e.g. Pickett 1989, Blois et al. 2013). It is an untested assumption that you can substitute space for time in analyzing for future evolutionary changes.

Second, the conclusions of the Bay et al. paper rest on an assumption that you have adequate data on the genetics involved in change and on the demography of the species. A clear understanding of the ecology of the species and what limits its distribution and abundance would seem to be prerequisites for understanding the mechanisms of how evolutionary changes might occur.

The third assumption is that, if there is a correlation between the genetic measures and the climate or vegetation indices, one can identify the precise ‘genomic vulnerability’ of the local population. Genomic variation was most closely related to precipitation variables at each site. The geographic area with one of the highest scores in genomic vulnerability was in the desert area of the intermountain west (USA). As far as I can determine from their Figure 1, there was only one sampling site in this whole area of the intermountain west. Finally Bay et al. (2018) compared the genomic vulnerability data to the population changes reported for each site. Population changes for each sampled site were obtained from the North American Breeding Bird Survey data from 1996 to 2012.

The genetic data and its analysis are more impressive, and since I am not a genetics expert I will simply give it a A grade for genetics. It is the ecology that worries me. I doubt that the North American Breeding Bird Survey is a very precise measure of population changes in any particular area. But following the Bay et al. paper, assume that it is a good measure of changing abundance for the yellow warbler. From the Bay et al. paper abstract we see this prediction:

“Populations requiring the greatest shifts in allele frequencies to keep pace with future climate change have experienced the largest population declines, suggesting that failure to adapt may have already negatively affected populations.”

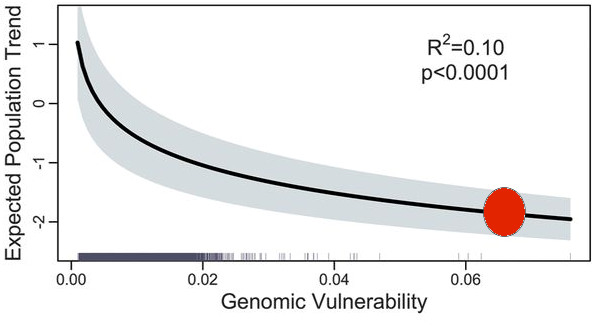

The prediction is illustrated in Figure 1 below from the Bay et al. paper.

Figure 1. From Bay et al. (2018) Figure 2C. (Red dot explained below).

Figure 1. From Bay et al. (2018) Figure 2C. (Red dot explained below).

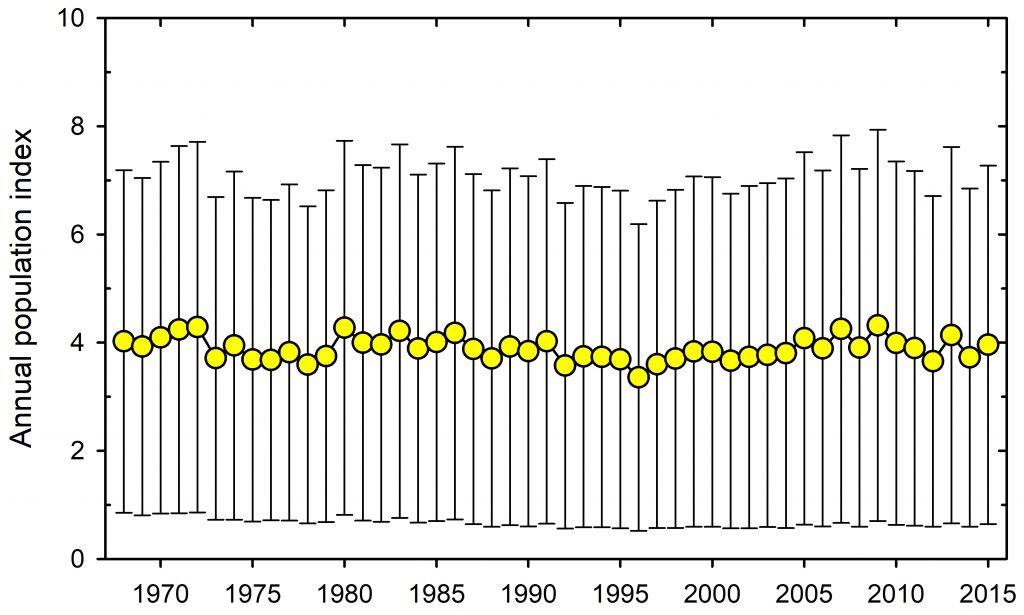

Consider a single case, the Great Basin, area S09 of the Sauer et al. (2017) breeding bird surveys. From the map in Bay et al. (2018) Figure 2 we get the prediction of a very high genomic vulnerability (above 0.06, approximate red dot in Figure 1 above) for the Great Basin, and thus a strongly declining population trend. But if we go to the Sauer et al. (2017) database, we get this result for the Great Basin (Figure 2 here), a completely stable yellow warbler population for the last 45 years.

Figure 2. Data for the Great Basin populations of the Yellow Warbler from the North American Breeding Bird Survey, 1967 to 2015 (area S09). (From Sauer et al. 2017)

One clue to this discrepancy is shown in Figure 1 above where R2 = 0.10, which is to say the predictability of this genomic model is near zero.

So where does this leave us? We have what appears to be an A grade genetic analysis coupled with a D- grade ecological model in which explanations are not based on any mechanism of population dynamics, so that the model presented is useless for any predictions that can be tested in the next 10-20 years. I am far from convinced that this is a useful exercise. It would be a good paper for a graduate seminar discussion. Marvelous genetics, very poor ecology.

And as a footnote I note that mammalian ecologists have already taken a different but more insightful approach to this whole problem of climate-driven adaptation (Boutin and Lane 2014).

Bay, R.A., Harrigan, R.J., Underwood, V.L., Gibbs, H.L., Smith, T.B., and Ruegg, K. 2018. Genomic signals of selection predict climate-driven population declines in a migratory bird. Science 359(6371): 83-86. doi: 10.1126/science.aan4380.

Blois, J.L., Williams, J.W., Fitzpatrick, M.C., Jackson, S.T., and Ferrier, S. 2013. Space can substitute for time in predicting climate-change effects on biodiversity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 110(23): 9374-9379. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1220228110.

Boutin, S., and Lane, J.E. 2014. Climate change and mammals: evolutionary versus plastic responses. Evolutionary Applications 7(1): 29-41. doi: 10.1111/eva.12121.

Pickett, S.T.A. 1989. Space-for-Time substitution as an alternative to long-term studies. In Long-Term Studies in Ecology: Approaches and Alternatives. Edited by G.E. Likens. Springer New York, New York, NY. pp. 110-135.

Sauer, J.R., Niven, D.K., Hines, J.E., D. J. Ziolkowski, J., Pardieck, K.L., and Fallon, J.E. 2017. The North American Breeding Bird Survey, Results and Analysis 1966 – 2015. USGS Patuxent Wildlife Research Center, Laurel, MD. https://www.mbr-pwrc.usgs.gov/bbs/