If there is one important element missing in many of our current ecological paradigms it is long-term studies. This observation boils down to the lack of proper controls for our observations. If we do not know the background of our data sets, we lack critical perspective on how to interpret short-term studies. We should have learned this from paleoecologists whose many studies of plant pollen profiles and other time series from the geological record show that models of stability which occupy most of the superstructure of ecological theory are not very useful for understanding what is happening in the real world today.

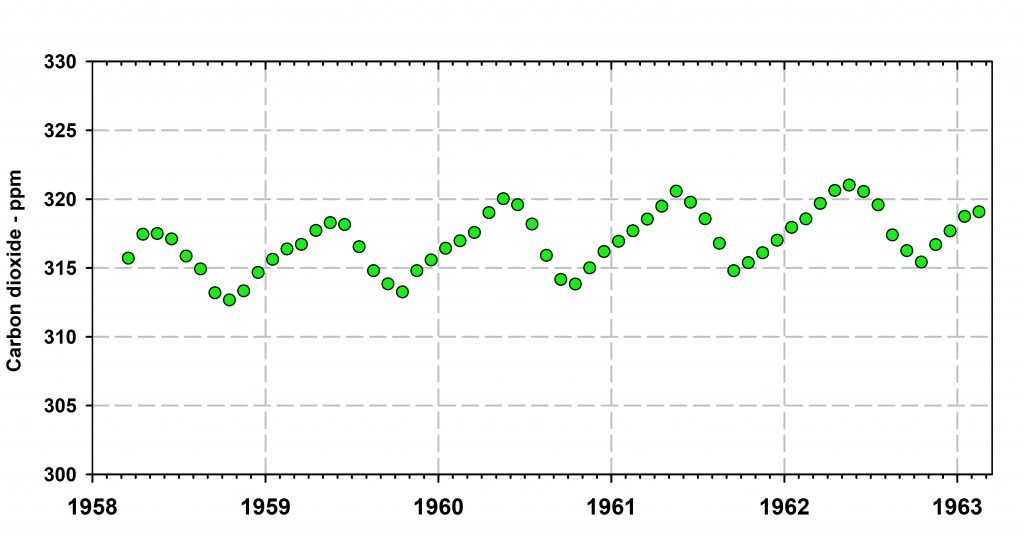

All of this got me wondering what it might have been like for Charles Keeling when he began to measure CO2 levels on Mauna Loa in Hawaii in 1958. Let us do a thought experiment and suggest that he was at that time a typical postgraduate students told by his professors to get his research done in 4 or at most 5 years and write his thesis. These would be the basic data he got if he was restricted to this framework:

Keeling would have had an interesting seasonal pattern of change that could be discussed and lead to the recommendation of having more CO2 monitoring stations around the world. And he might have thought that CO2 levels were increasing slightly but this trend would not be statistically significant, especially if he has been cut off after 4 years of work. In fact the US government closed the Mauna Loa observatory in 1964 to save money, but fortunately Keeling’s program was rescued after a few months of closure (Harris 2010).

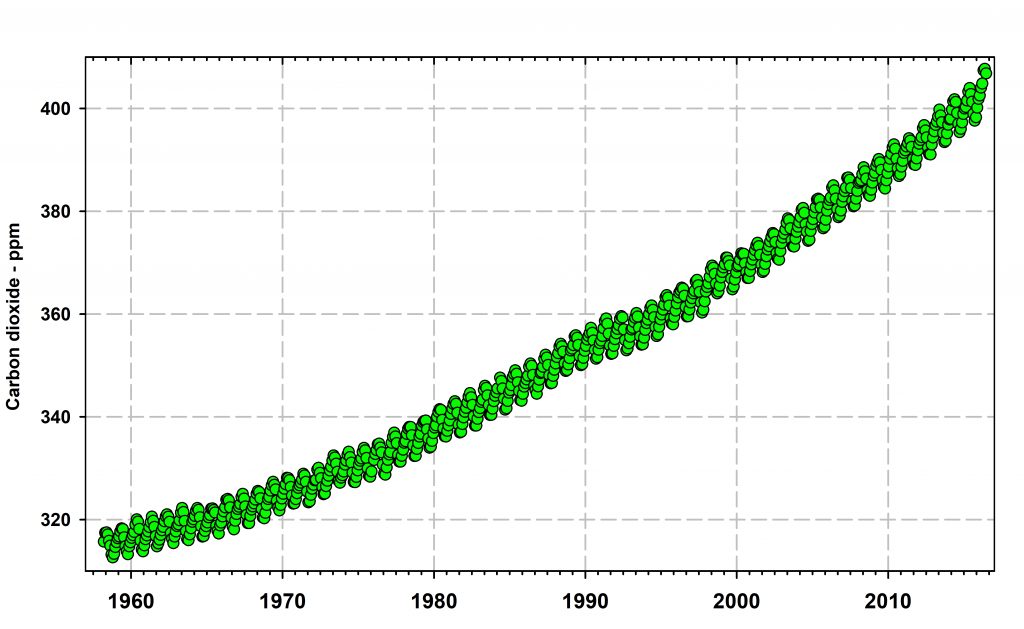

Charles Keeling could in fact be a “patron saint” for aspiring ecology graduate students. In 1957 as a postdoc he worked on developing the best way to measure CO2 in the air by the use of an infrared gas analyzer, and in 1958 he had one of these instruments installed at the top of Mauna Loa in Hawaii (3394 m, 11,135 ft) to measure pristine air. By that time he had 3 published papers (Marx et al. 2017). By 1970 at age 42 his publication list had increased to a total of 22 papers and an accumulated total of about 50 citations to his research papers. It was not until 1995 that his citation rate began to exceed 100 citations per year, and after 1995 at age 67 his citation rate increased very much. So, if we can do a thought experiment, in the modern era he could never even apply for a postdoctoral fellowship, much less a permanent job. Marx et al. (2017) have an interesting discussion of why Keeling was undercited and unappreciated for so long on what is now considered one of the world’s most critical environmental issues.

What is the message for mere mortals? For postgraduate students, do not judge the importance of your research by its citation rate. Worry about your measurement methods. Do not conclude too much from short-term studies. For professors, let your bright students loose with guidance but without being a dictator. For granting committees and appointment committees, do not be fooled into thinking that citation rates are a sure metric of excellence. For theoretical ecologists, be concerned about the precision and accuracy of the data you build models about. And for everyone, be aware that good science was carried out before the year 2000.

And CO2 levels yesterday were 407 ppm while Nero is still fiddling.

Harris, D.C. (2010) Charles David Keeling and the story of atmospheric CO2 measurements. Analytical Chemistry, 82, 7865-7870. doi: 10.1021/ac1001492

Marx, W., Haunschild, R., French, B. & Bornmann, L. (2017) Slow reception and under-citedness in climate change research: A case study of Charles David Keeling, discoverer of the risk of global warming. Scientometrics, 112, 1079-1092. doi: 10.1007/s11192-017-2405-z