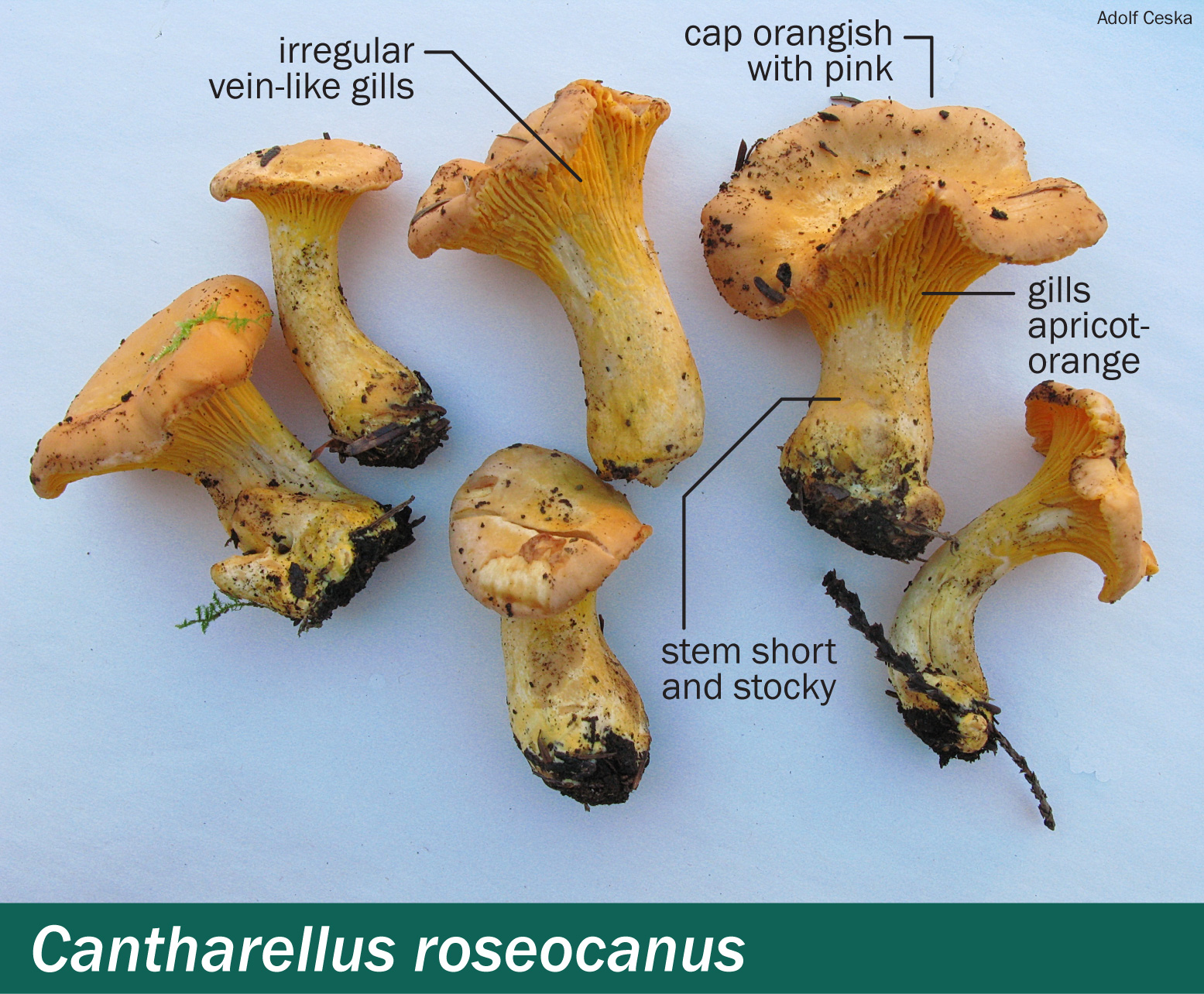

Cantharellus roseocanus — Rainbow chanterelle

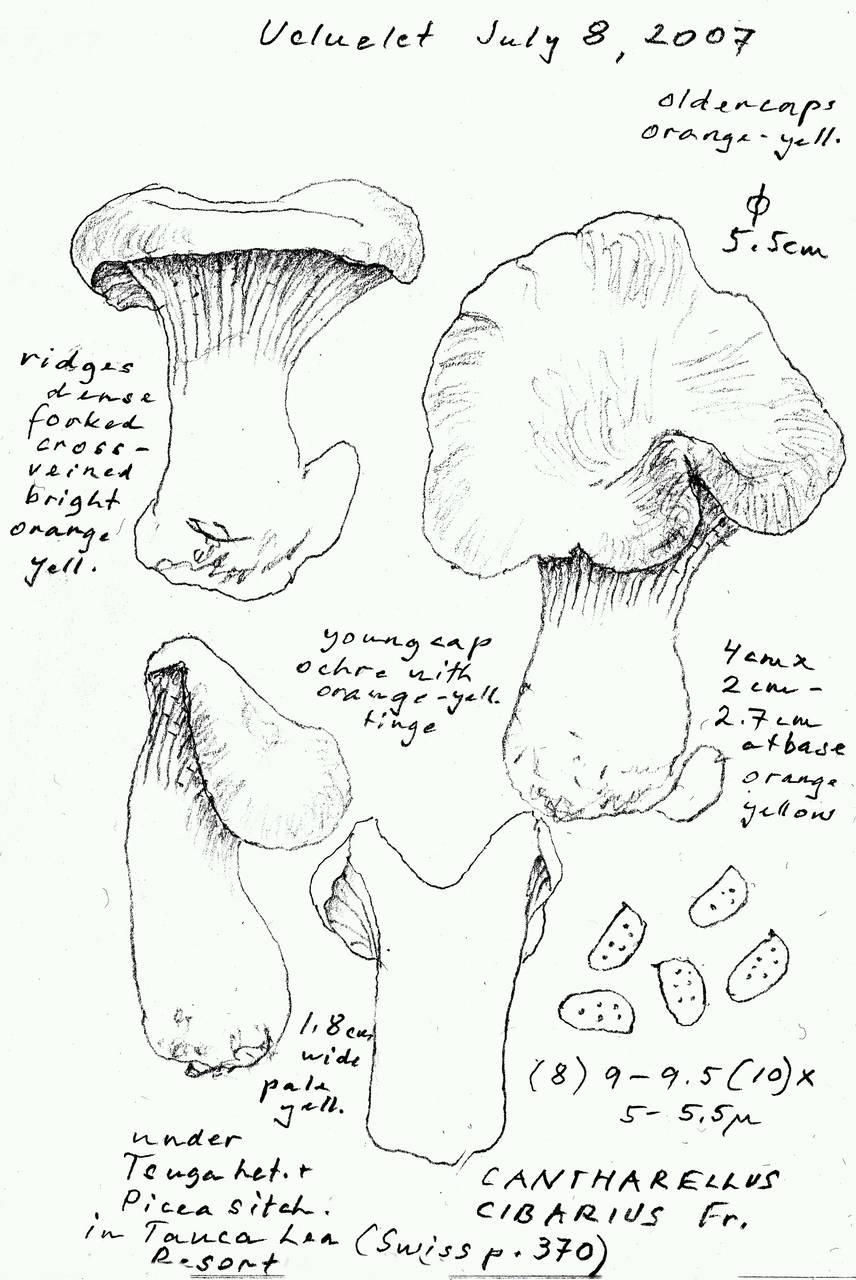

Rainbow chanterelle2, sketches by Oluna Ceska.

Odour: Fruity.

Taste: Pleasant.

Cap: 2–12 cm in diameter, convex or flattened with the margins inrolled towards the stem. With age, the cap becomes a little depressed in the centre, and the margin becomes more wavy and lobed. The background colour is orangish, with pink at the margin, and with a grayish bloom when young and dry. The surface is smooth.

Gills: Decurrent, shallow, light-coloured veins appearing as ridges that run down from the underside of the cap onto the upper stem, easily peeled from cap. Chanterelle veins are thicker and further apart than the gills of most mushrooms and they fork and are connected by cross veins. Vein colour of the rainbow chanterelle varies from light yellow when young to apricot orange with age.

Stem: 1.5–10 cm long x 1.5–3 cm wide, typically short and rather stocky; often shorter than the cap is wide. The colour is white to yellowish and contrasts with the colour of the ridges.

Ring: None.

Cup: None.

Spores: 7.5–10 x 4.5–5.5 µm, smooth and white.

Habitat: On the ground in clumps or in troops, often under Sitka spruce (Picea sitchensis), ectomycorrhizal.

Geographical distribution: A western North American species5 with records from British Columbia to Mexico.

The scaly or woolly chanterelle, Turbinellus floccosus (=Gomphus floccosus) is more deeply trumpet-shaped than the hybrid chanterelle and it has a scaly top. The scaly chanterelle is not recommended as an edible; although some do eat it6. It can contain norcaperatic acid7, which may be responsible for gastrointestinal distress with stomach cramps8.

Hygrophoropsis aurantiaca (false chanterelle) may be mildly poisonous6. It can be distinguished from the rainbow chanterelle by its thinner flesh and stalk, and by its thin gills, which do not usually fuse with one another.

Omphalotus species, jack-o-lantern mushrooms, are poisonous, containing toxins including muscarine. Although jack-o-lantern mushrooms have been confused with chanterelles, they differ in that their gills are narrower and deeper and they grow from wood, not from the ground. Omphalotus has yet to be reported from BC and the few records from Oregon and Washington have yet to be verified1. Jack-o-lantern mushrooms have resulted in poisonings in California and if they become more common further north, they have the potential to cause accidental poisonings in the Pacific northwest and BC8.

Treatment: Contact your regional Poison Control Centre if you or someone you know is ill after eating chanterelles. Poison centres provide free, expert medical advice 24 hours a day, seven days a week. If possible, save the mushrooms or some of the leftover food containing the mushrooms to help confirm identification.

Poison Control:

British Columbia: 604-682-5050 or 1-800-567-8911.

United States (WA, OR, ID): 1-800-222-1222.