Our iPhones teach us very subtly to have great faith in technology. This leads the public at large to think that technology will solve large issues like greenhouse gases and climate change. But for scientists we should remember that technology must be looked at very carefully when it tells us we have a shortcut to ecological measurement and understanding. For the past 35 years satellite data has been available to calculate an index of greening for vegetation from large landscapes. The available index is called NDVI, normalized difference vegetation index, and is calculated as a ratio of near infrared light to red light reflected from the vegetation being surveyed. I am suspicious that NDVI measurements tell ecologists anything that is useful for the understanding of vegetation dynamics and ecosystem stability. Probably this is because I am focused on local scale events and landscapes of hundreds of km2 and in particular what is happening in the forest understory. The key to one’s evaluation of these satellite technologies most certainly lies in the questions under investigation.

A whole array of different satellites have been used to measure NDVI and since the more recent satellites have different precision and slightly different physical characteristics, there is some problem of comparing results from different satellites in different years if one wishes to study long-term trends (Guay et al. 2014). It is assumed that NDVI measurements can be translated into aboveground net primary production and can be used to start to answer ecological questions about seasonal and annual changes in primary production and to address general issues about the impact of rising CO2 levels on ecosystems.

All inferences about changes in primary production on a broad scale hinge on the reliability of NDVI as an accurate measure of net primary production. Much has been written about the use of NDVI measures and the need for ground truthing. Community ecologists may be concerned about specific components of the vegetation rather than an overall green index, and the question arises whether NDVI measures in a forest community are able to capture changes in both the trees and the understory, or for that matter in the ground vegetation. For overall carbon capture estimates, a greenness index may be accurate enough, but if one wishes to determine whether deciduous trees are replacing evergreen trees, NDVI may not be very useful.

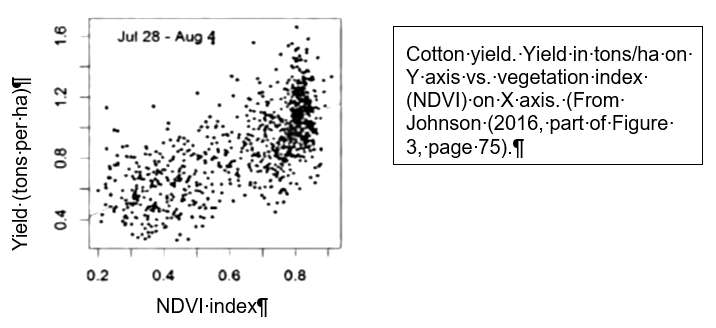

How can we best validate satellite based estimates of primary productivity? To do this on a landscape scale we need to have large areas with ground truthing. Field crops are one potential source of such data. Kang et al. (2016) used crops to quantify the relationship between remotely sensed leaf-area index and other satellite measures such as NDVI. The relationships are clear in a broad sense but highly variable in particular, so that the ability to predict crop yields from satellite data at local levels is subject to considerable error. Johnson (2016, Fig. 6, p. 75) found the same problem with crops such as barley and cotton (see sample data set below). So there is good news and bad news from these kinds of analyses. The good news is that we can have extensive global coverage of trends in vegetation parameters and crop production, but the bad news is that at the local level this information may not be helpful for studies that require high precision for example in local values of net primary production. Simply to assume that satellite measures are accurate measures of ecological variables like net aboveground primary production is too optimistic at present, and work continues on possible improvements.

Many of the critical questions about community changes associated with climate change cannot in my opinion be answered by remote sensing unless there is a much higher correlation of ground-based research that is concurrent with satellite imagery. We must look critically at the available data. Blanco et al. (2016) for example compared NDVI estimates from MODIS satellite data with primary production monitored on the ground in harvested plots in western Argentina. The regression between NDVI and estimated primary production had R2 values of 0.35 for the overall annual values and 0.54 for the data restricted to the peak of annual growth. Whether this is a satisfactory statistical association is up to plant ecologists to decide. I think it is not, and the substitution of p values for the utility of such relationships is poor ecology. Many more of these kind of studies need to be carried out.

The advent of using drones for very detailed spectral data on local study areas will open new opportunities to derive estimates of primary production. For the present I think we should be aware that NDVI and its associated measures of ‘greenness’ from satellites may not be a very reliable measure for local or landscape values of net primary production. Perhaps it is time to move back to the field and away from the computer to find out what is happening to global plant growth.

Blanco, L.J., Paruelo, J.M., Oesterheld, M., and Biurrun, F.N. 2016. Spatial and temporal patterns of herbaceous primary production in semi-arid shrublands: a remote sensing approach. Journal of Vegetation Science 27(4): 716-727. doi: 10.1111/jvs.12398.

Guay, K.C., Beck, P.S.A., Berner, L.T., Goetz, S.J., Baccini, A., and Buermann, W. 2014. Vegetation productivity patterns at high northern latitudes: a multi-sensor satellite data assessment. Global Change Biology 20(10): 3147-3158. doi: 10.1111/gcb.12647.

Johnson, D.M. 2016. A comprehensive assessment of the correlations between field crop yields and commonly used MODIS products. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 52(1): 65-81. doi: 10.1016/j.jag.2016.05.010.

Kang, Y., Ozdogan, M., Zipper, S.C., Roman, M.O., and Walker, J. 2016. How universal Is the relationship between remotely sensed vegetation Indices and crop leaf area Index? A global assessment. Remote Sensing 2016 8(7): 597 (591-529). doi: 10.3390/rs8070597.

Thanks for above important article what I found since months and I got now from your site.

I am going to bookmark this page.

Thanks again,

Regards,

Sumra

http://www.sumra.in

Great impacts of Technology.

great Article

Looking forward to future post