Peru Colombia Ecuador Costa Rica Rwanda Equatorial Guinea

Back to Home

Relevant publications from

each project shown below with graduate(*) and undergraduate(§)

student co-authors

Manu Biosphere

Reserve, Peru

|

A primary goal in

our research is to

understand spatial patterns

of species diversity in the

tropical Andes. In the Manu

Biosphere Reserve, we use

audio-visual counts and mist

nets to survey birds along a

3000-m elevational gradient,

ranging from the Amazon

basin to treeline

(400-3400m). We use these

data to quantify avian

richness and species

turnover, and to assess how

landscape heterogeneity,

influenced by landslide

disturbance, contributes to

these diversity patterns.

These data also serve as

training and test data for

modeling species' response

curves with elevation and

for comparisons of diversity

patterns to other taxa. We have documented extremely high species turnover along tropical elevational gradients, with 100% change in community composition in 500 m elevation (twice as high as the rate of species turnover along temperate mountainsides in the Eastern US). Patterns of species turnover in birds correspond to changes in tree communities and to structural components of vegetation. The position of the cloud bank and gradients in moisture are also important predictors of community composition in these regions, factors we can expect to be altered by climate change. *Scholer, M.N., Jankowski, J.E. (2019) New and noteworthy distributional records for birds of the Manu Biosphere Reserve. Cotinga 41: 87–90. Jankowski, J.E., Londoño, G.A., Robinson, S.K., Chappell, M.A. (2013) Exploring the role of physiology and biotic interactions in determining elevational ranges of tropical animals. Ecography. 36: 1-12 (Editor’s Choice) Jankowski, J.E., Merkord, C.L., Rios, W.F., Cabrera, K.C., Salinas R., N., Silman, M.R. (2013) The relationship of tropical bird communities to tree species composition and vegetation structure along an Andean elevational gradient. Journal of Biogeography. 40: 950-962. See other publications (first authored by assistants) from the Manu Project here |

Cloud forest after a mid-afternoon

rainstorm in Manu at 1700 m

|

|

Tropical mixed-species flocks:

social systems within bird communities

Mixed-species flocks occur

in almost all bird communities

globally, but nowhere are they as

diverse and complex as in tropical

forest. Our research has

characterized mixed-species flocking

from multiple perspectives, asking

the following: How does the

diversity, stability and composition

of flocks change from lowland Amazon

to high Andean forest? Which species

in flocks are responsible for flock

movements and cohesion? Do certain

traits favor participation in

mixed-species flocks as a strategy

to increase foraging efficiency or

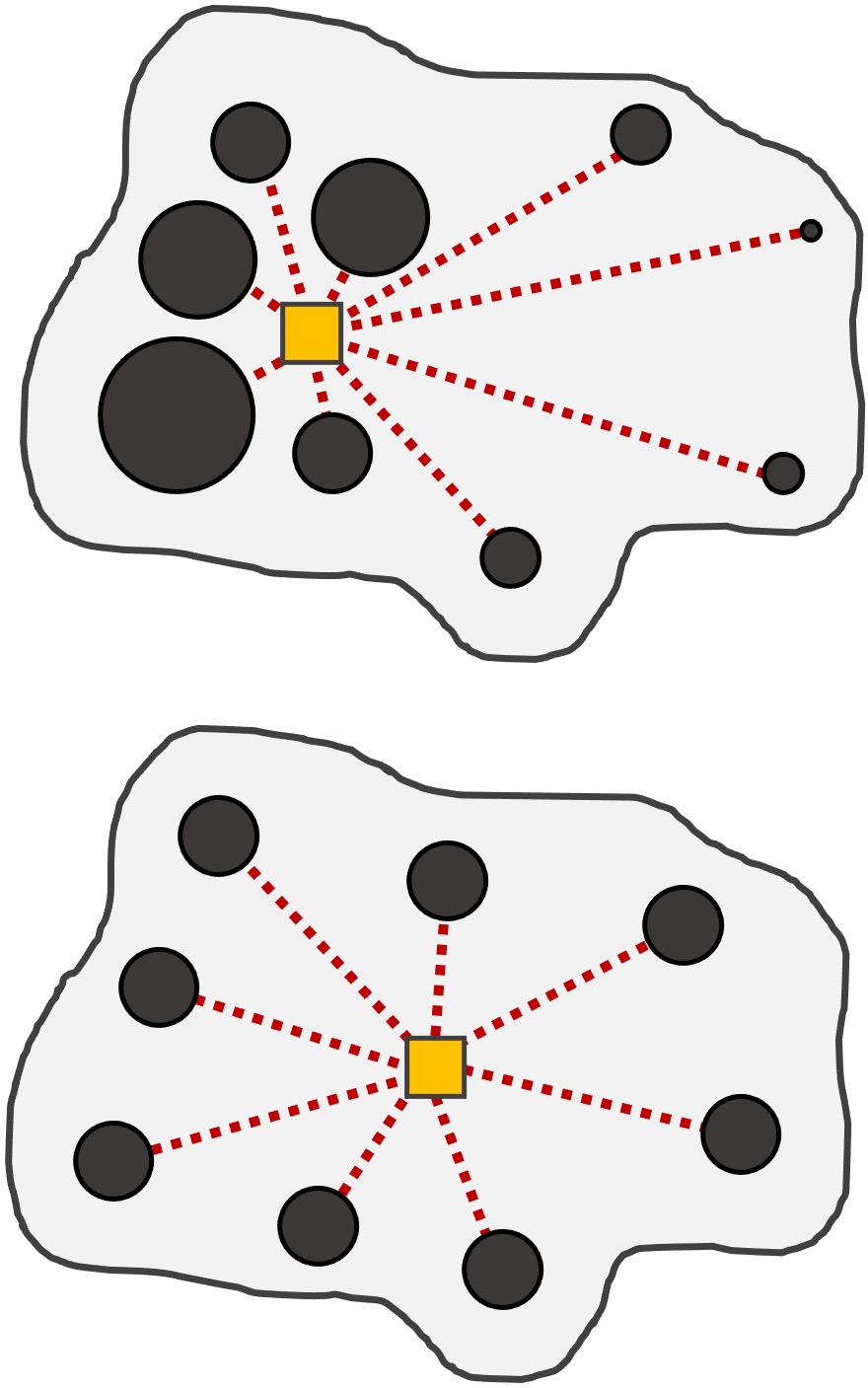

reduce predation risk? Our work has revealed that mixed-species flocks exist as distinct sub-units of tropical bird communities across elevations, with each flock type directed by a core group of species responsible for flock cohesion. Species within flocks tend to exhibit a suite of similar traits and behaviors -- small to medium-bodied species with low dispersal ability foraging in low- to mid-forest strata -- traits typically associated with increased vulnerability to predation. At all elevations, mixed-species flocks maintain stable foraging territories across seasons and years.  |

(Top) Core species of lower montane flocks, including insectivores and omnivores, Chlorospingus, Chlorochrysa, Leptopogon, Myioborus and Tangara species. Mixed-flocking species (bottom left) occupy a much smaller area of trait space compared with the overall bird community (bottom right), with flocking species represented by small- to medium-bodied species with lower dispersal ability. *Muñoz, J., Jankowski, J.E. (2023) Neotropical mixed-species bird flocks in a community context. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 378(1878): 20220104. DOI: 10.1098/rstb.2022.0104. Special Issue *Muñoz, J., Allen, J.M., Kolencik, S., Londoño, G.A., Jankowski, J.E. (in prep) Parasite transmission in mixed-species flocks: When birds of different feathers flock together. |

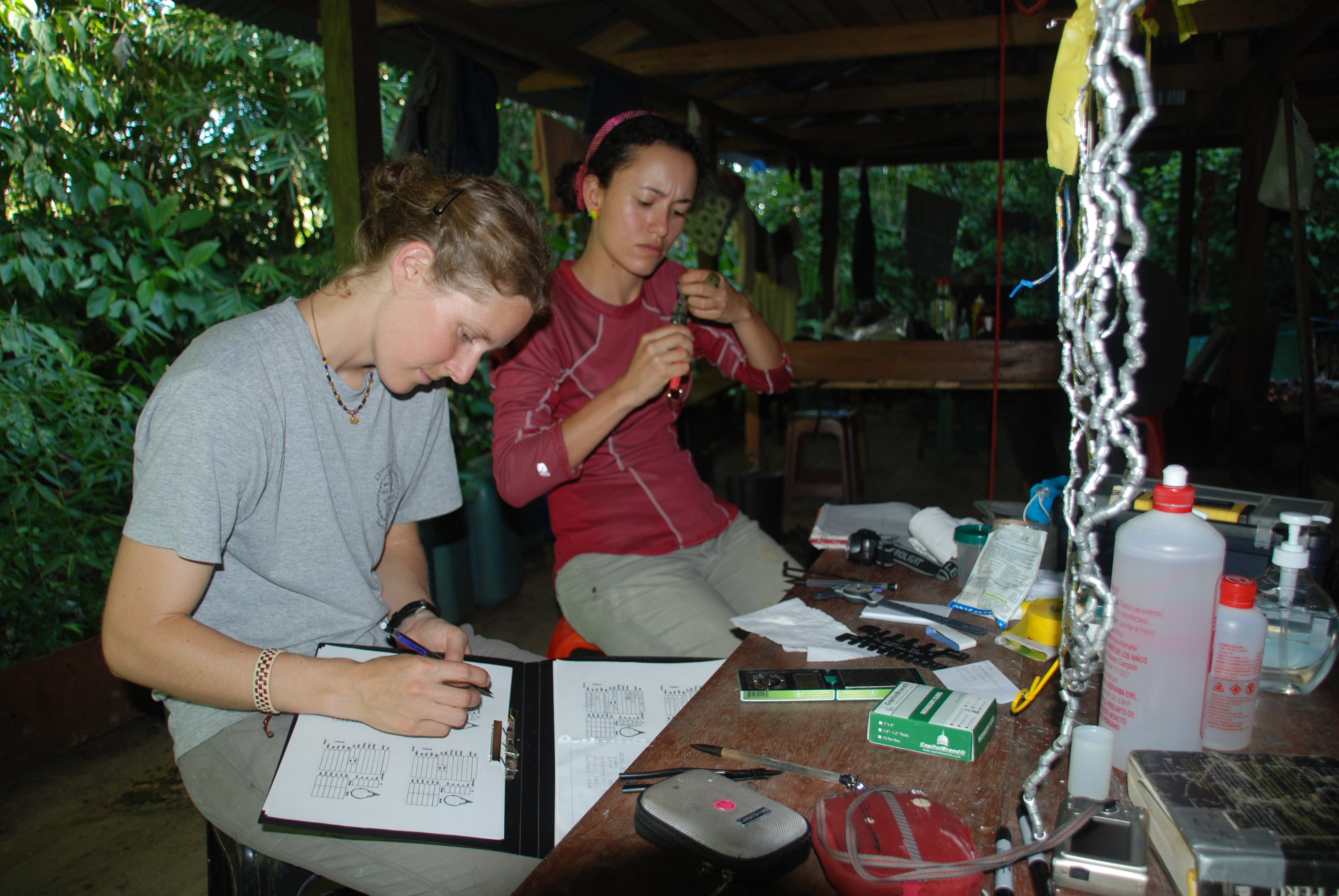

Jill Jankowski and Jenny Munoz banding in Pantiacolla, 2011, when we began work to measure metabolic traits of Peruvian birds. |

The 'Pace

of Life' in the Tropics

To

test whether abiotic factors, such as

temperature, constrain species to particular

altitudes, we measured metabolic rates and body

temperature for >200 tropical bird species.

We found significant differences across

elevation in key indices of thermal physiology –

thermal conductance, body temperature and lower

critical temperatures (LCT) – suggesting that

highland species are more resistant to heat loss

than lowland species – but

little evidence that limits to thermal tolerance

(acute or long term) are sufficient to restrict

species’ elevational ranges.

Using our database of banded birds, in a study led by Micah Scholer, we estimated annual survival for nearly 40 species, the largest dataset on tropical birds to date, filling a critical gap in our understanding of the ‘pace of life’ of tropical birds. We revealed that adult survival is negatively associated with BMR and elevation – species with higher metabolic demands that live at high elevation have lower survival. Thus, lower BMR appears to be an intrinsic characteristic of the slow pace-of-life of tropical birds, and birds living at higher elevations may be characterized by a unique suite of traits where BMR does not differ from lowland species, but survival does. *Scholer, M.N., *Strimas-Mackey, M., Jankowski, J.E. (2020) A meta-analysis of global avian survival across species and latitude. Ecology Letters DOI: 10.1111/ele.13573 *Scholer, M.N., Arcese, P., Puterman, M. L., Londoño, G.A., Jankowski, J.E. (2019) Survival is negatively related to basal metabolic rate in tropical Andean birds. Functional Ecology 00: 1–10. DOI: 10.1111/1365-2435.13375 *Scholer, M.N., Merkord, C.L., Londoño, G.A., Jankowski, J.E. (2018) Minimum longevity estimates for some Neotropical land birds of southeastern Peru. Wilson Journal of Ornithology. DOI: 10.1676/17-095.1 Londoño, G.A., Chappell, M.A., Jankowski, J.E. and Robinson, S.K. (2017) Do thermoregulatory costs limit altitude distributions of Andean forest birds? Functional Ecology 31: 204–215 DOI:10.1111/1365-2435.12697 Londoño, G.A., Chappell, M.A., del Rosario Castañeda, M., Jankowski, J.E., Robinson, S.K. (2014) Basal metabolism in tropical birds: Latitude, altitude, and the “Pace of Life” Functional Ecology DOI:10.1111/1365-2435.12348. |

Eutoxeres condamini is found in lower montane forest of Manu National Park. Based on its bill morphology, we expect this species to be specialized to flowering plant genera (e.g., Centropogon, shown here). Photo: Julian Heavyside. |

Hummingbirds

and Flowering Plants in the Andes The

highest diversity of hummingbirds is found in the

Andes of South America, where species have

elevational ranges of only a few hundred meters.

Despite well-studied specialization to

flowering-plants in some species, no one has

examined how relationships between hummingbirds

and flowering plants may constrain hummingbird

species’ elevational distributions. One advantage

of hummingbirds is that they leave a record of

which flowers they visit through accumulation of

pollen on their bills and heads. We are using the Neotropical

Pollen Database developed by the Palynology

lab of Mark Bush to help identify pollen samples

collected from bills of captured hummingbirds

across elevations in Manu and to describe dietary

composition for >30 species.

Combined with data on occurrence of hummingbird and flowering-plant species along the same gradient, we ask: Do range limits in hummingbirds coincide with limits in the distribution of their flowering plants? Do hummingbirds with broad distributions change their use of flowering-plant resources with elevation? Are specialist hummingbirds constrained to narrower elevational ranges compared to generalists? Our lab is working with species like Sicklebills (photo left) and the evolution of curvature in flower corollas, and territoriality and spatial use by high elevation hummingbirds like the Shining Sunbeam. *Boehm, M., §Guevara Apaza, D., Jankowski, J.E., Cronk, Q. (2022) Floral phenology of an Andean bellflower and pollination by Buff-tailed Sicklebill hummingbird. Ecology and Evolution 12(6): e8988. *Boehm, M., Jankowski, J.E., Cronk, Q. (2022) Plant-pollinator specialization: Origin and measurement of curvature. American Naturalist 199(2): 206–222. §Pavan, L., *Hazlehurst, J., Jankowski, J.E. (2020) Patterns of territorial space utilization in a tropical montane hummingbird (Aglaeactis cupripennis). Journal of Field Ornithology.00: 1–12. DOI: 10.1111/jofo.12321 §Cespedes, L., §Pavan, L., *Hazlehurst, J., Jankowski, J.E. (2019) The behavior and diet of the shining sunbeam (Trochilidae): A territorial, high elevation hummingbird. Wilson Journal of Ornithology 131: 24-34. DOI: 10.1676/18-79.1 *Boehm, M., *Scholer, M., *Kennedy, J., *Heavyside, J., Daza, A., §Guevara-Apaza, D., Jankowski, J. (2018) The Manú Gradient as a study system for bird pollination. Biodiversity Data Journal 6: e22241. DOI: 10.3897/BDJ.6.e22241 *David, S., Jankowski, J.E., Londoño, G.A. (2018) Combining multiple sources of data to uncover the natural history of an endemic Andean hummingbird: The Peruvian Piedtail. Journal of Field Ornithology 89: 315-325. §Dyck-Chan, L., *David, S., Jankowski, J.E. (in revision for Journal of Field Ornithology) Resource specialization and range overlap of tropical hermit hummingbirds. |

|

Andean

birds

and vegetation: remotely

sensed

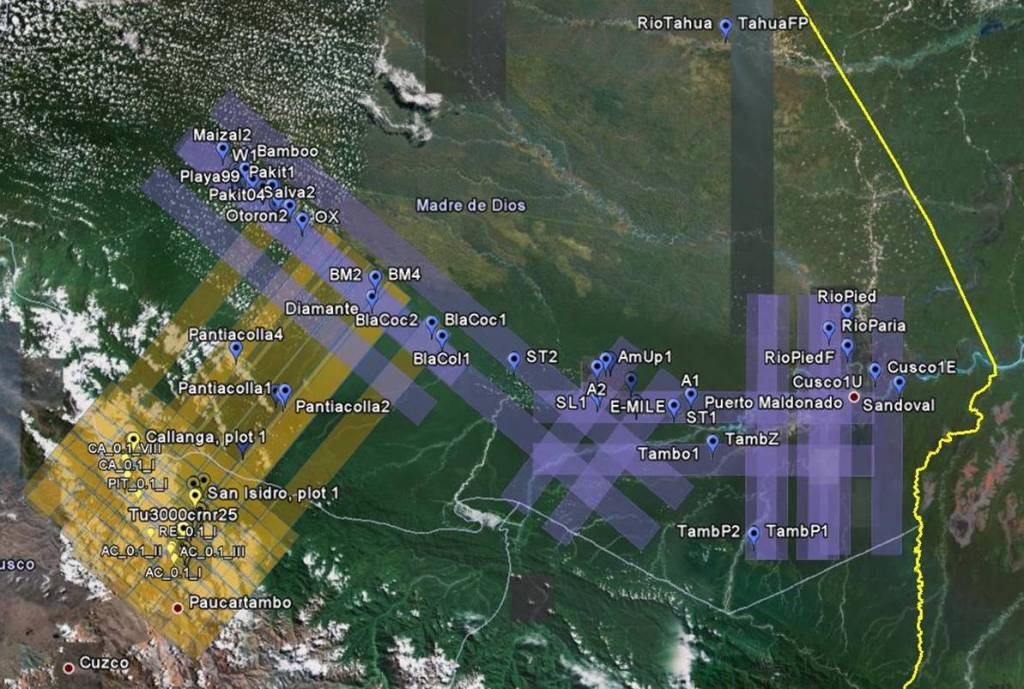

data for distribution modeling and diversity mapping

The study of biodiversity in tropical montane forest has long been plagued by an inability to access and sample the heterogeneity of these landscapes. Birds are among the most well studied taxa, yet even the most detailed studies of avian distribution in tropical mountains describe elevational ranges by limits of occurrence along single transects, or estimated abundance based on limited spatial sampling. For birds, we know that vegetation structure and complexity are important predictors of species richness and are used in habitat selection for individual species, but ground-based vegetation sampling is time-consuming, spatially limited and sometimes dangerous in steep mountainous terrain. Advances in remote sensing now allow detailed, quantitative measures of vegetation gathered over thousands of square kilometers, which will be enormously useful for understanding patterns of diversity and distributions. This project aims to combine our data on tropical bird abundances along the elevational gradient in Manu with iterferometric Synthetic Aperature Radar (inSAR) data for the study area. Using variables derived from radar (e.g., canopy height, above-ground biomass), we can generate landscape-scale predictions for bird species richness, variation in species composition (beta diversity) and individual species' distributions in Andean landscapes, including population size estimates for the best modeled species. Our goal is to use remote sensing and GIS applications to construct informative maps of spatial patterns of avian diversity for the montane regions of Manu. |

Overview of Departments of Cusco and Madre de Dios, Peru. Yellow and blue swaths indicate flight paths for remotely sensed radar data. The yellow swaths, collected in July 2009 by Earth Data, Inc., cover the montane portion of the Manu region. |

| Ectoparasites of Andean

birds An

assortment of ectoparasites live on birds, among which are

chewing lice specialized to wing and body

feathers. These parasites can track the

evolutionary histories of their hosts, though this

occurs in differing degrees of cospeciation. Such

relationships give us the opportunity to study

microevolutionary processes in bird hosts at regional spatial

scales, such

as dispersal, gene flow and population

divergence, as well as macroevolutionary

patterns of host-parasite coevolution in species

groups distributed across biogeographic provinces.

As part of our research in Manu, we collected ectoparasites from captured birds using feather dusting. With these data, we are joining forces with bird lice experts and collections at Virginia Tech and the Field Museum of Chicago to investigate micro- and macroevolutionary patterns in Amazonian and Andean birds. §Soto Patiño, J. Londoño, G.A., Johnson, K.P., Wechstein, J.W., Avendaño, J.E., Jankowski, J.E., Catanach, T.A., Sweet, A.D., Allen, J. (2018) Composition and distribution of lice (Insecta: Phthiraptera) on Colombian and Peruvian birds: New data on louse-host associations in the Neotropics. Biodiversity Data Journal 6: e21635 DOI: 10.3897/BDJ.6.e21635. |

Crowned Chat-Tyrant

(Ochthoeca spodionota) was feeding nestlings near

treeline at 3400 meters. Perhaps this constrained

time available for preening, leaving feathers

susceptible to chewing lice. Note the barbs on

chest contour feathers have been completely

eaten, leaving only the rachii.

|

Cloud forest habitats

are moisture-saturated, resulting in moss-laden

tree trunks and unmatched epiphyte diversity and

abundance. Our study shows that range boundaries

of numerous bird species coincide with the lower

limit of cloud forest along the steep biophysical

gradients of the Pacific slope.

|

Endemism,

beta-diversity, and consequences of climate

change in Central American cloud forests

The leeward Pacific slope of the Tilaran Mountains offers a unique opportunity to examine the effect of steep biophysical gradients on the organization of biodiversity. A central feature of this gradient is the "cloud forest margin" which is characterized by major shifts in vegetation structure and punctuated species turnover. This mountain range also exhibits extraordinarily high levels of endemism, harboring numerous species limited to Central America and an even greater proportion of species limited to the Costa Rican - Panamanian highlands. The combination of climate warming and regional deforestation are expected to generate warming and drying effects on the cloud forests of this region, adding to the need for urgent and precisely placed conservation efforts. Our research of the bird and tree communities of this landscape spans a decade, in which time we have quantified the diversity of avian and tree communities and the correlative effects of temperature and moisture on species composition along the gradient. We have found that many narrowly endemic birds tend to be numerically rare, in addition to being habitat specialists, creating a "syndrome of rarity" for many cloud forest inhabitants. Our yearly censusing of the bird community now allows us to assess yearly variation in abundances of cloud forest species and to provide critical data for analysis of population viability for endemic species. Jankowski, J.E., Kyle, K.O., Ciecka, A.L., Gasner, M., Rabenold, K.N. (2021) Response of avian communities to edges of tropical montane forests: Implications for the future of endemic habitat specialists. Global Ecology and Conservation 30: e01776. DOI: 10.1016/j.gecco.2021.e01776 Gasner, M.R., Jankowski, J.E., Ciecka, A.L., Kyle, K.O., Rabenold, K.N. (in prep for Ecological Applications) Population variability in tropical birds and implications for the design of monitoring studies. Gasner, M.R., Jankowski, J.E., Ciecka, A.L., Kyle, K.O., Rabenold, K.N. (2010) Projecting impacts of climate change on Neotropical montane forests. Biological Conservation 143: 1250-1258. Jankowski, J. E., Ciecka, A.L, Meyer, N.Y., Rabenold, K.N. (2009) Beta diversity along environmental gradients: Implications of habitat specialization in tropical montane landscapes. Journal of Animal Ecology 78: 315-327. Jankowski, J.E. & Rabenold, K.N. (2007) Endemism and local rarity in birds of Neotropical montane rainforest. Biological Conservation 138: 453-463. |

This Gray-breasted

Wood-Wren (Henicorhina leucophrys) replaces

the White-breasted

Wood-Wren

(H. leucosticta) in the Tilaran mountains of Costa Rica. Photo: Rosalbina Butron. |

Elevational

species replacements: Testing the interspecific

competition hypothesis in Neotropical birds

The phenomenon of elevational replacements between closely related species is well documented in tropical birds, especially in the Neotropics. It is assumed that interspecific competitive interactions underlie these replacements, preventing the coexistence of strong competitors. In his study of the Vilcabamba elevational gradient, Terborgh (1975) concluded that competitive interactions could limit the elevational ranges for up to 30% of montane birds. These conclusions were based primarily on distribution patterns of congeners along single gradients, with evidence for range expansion along mountain slopes where one congener was absent. Until now, experimental evidence to support the interspecific competition hypothesis in tropical mountains has been lacking. We used interspecific playback experiments to test for territorial behaviors between species in contact areas along elevational gradients. Aggressive territorial interactions between species would support the hypothesis that interspecific competition maintains these range boundaries in montane species exhibiting elevational replacements. Using recorded songs of target species, I conducted a series of playbacks (control, congener, and conspecific trials) to birds holding territories in replacement zones, and at increasing distances from these zones, where interspecific encounter rates decline precipitously. Results from the Tilaran mountains of Costa Rica show that species respond aggressively to congener songs in playback experiments where species come into contact along the gradient. As one moves away from the replacement zone, however, responses to congener songs grow weaker, and at distances well within the elevational ranges of these species, responses to congener songs cannot be distinguished from responses to negative control playbacks. While species in Costa Rica showed aggressive interactions with congeners at range boundaries, the strength of interspecific aggression varied between species and among genera, suggesting that some species could be behaviorally dominant. We emphasize that interspecific aggressive interactions at range boundaries, and especially asymmetries in interactions could pose constraints on species as they shift in response to changing climate regimes. Jankowski, J.E., Touchton, J.M., Graham, C.H., Robinson, S.K., Parra, J.L., Seddon, N., Tobias, J.A. (2012) The role of competition in structuring tropical bird communities. Ornitología Neotropical. 23: 115-124. Jankowski, J.E., Robinson, S.K., Levey, D.J. (2010) Squeezed at the top: Interspecific aggression may constrain elevational ranges in tropical birds. Ecology 91: 1877-1884. |

Yasuni - Papallacta, Ecuador

|

Stay tuned...

|

Nyungwe & Volcanoes National Park, Rwanda

| Taxonomic,

functional and phylogenetic diversity across

elevations With

our aim to describe the spatial

organization of diversity along

mountainsides, we draw comparisons between

different attributes of diversity and

community structure, incorporating both

functional and phylogenetic perspectives

on the changes in species richness and

beta diversity. Such functional and

phylogenetic diversity metrics can be used

to understand the relative strength of

underlying biotic and abiotic factors

affecting communities.

In collaboration with the Dian Fossey Gorilla Fund International (DFGFI) and African Parks, our analysis of bird communities in Nyungwe and Volcanoes National Parks shows that abiotic influences on community structure become more important towards high elevation, with reductions in the diversity and redundancy of functional roles observed in high elevation communities, particularly with the loss of large-bodied frugivores and insectivores. Across elevations, changes in species composition are dominated by species turnover at low to middle elevations, mostly due to the replacement of closely related lineages, with greater contributions of nestedness (richness-differences) toward the highest elevations. Thus, we tend to observe a transition from biotic to abiotic drivers underlying community structure as elevation increases. |

(Top left) Functional

trait space for 156 bird species in Nyungwe and

Volcanoes National Parks based on principal

components of eight morphological metrics, with

examples of functionally under- and over-dispersed

communities (Top right). (Bottom) Depiction of

changing avian communities with elevation, which

reflects both turnover and loss of species, with

corresponding changes in phylogenetic lineages and

functional traits represented in each elevational

zone.

|

Oyala, Equatorial Guinea

Lowland forest in

Equatorial Guinea is home to spectacular birds,

including this Yellow-bellied Wattle-eye and

Western Bluebill shown in the hand. These species

differ greatly in their feeding guild and

consequently, their functional roles in

Afrotropical forests.

|

Assessing the impacts of

forest degradation on birds in West-Central

Africa

Tropical landscapes often exist as a mosaic of intact old-growth forest and degraded or regenerating forest. It is critical to understand how these landscapes maintain biodiversity and ecosystem functioning. Because responses to habitat degradation are mediated by species’ traits, aspects of the environment (e.g., forest vegetation structure, microclimate) can impact how different functional groups respond to habitat perturbations. We can better understand how and why species respond to changes in habitat at the regional scale by evaluating how traits relate to those features at the local scale. A species’ realized niche is not only determined by its abiotic tolerances but also by biotic interactions. As such, investigating the ways in which communities express vulnerability to habitat change at different scales, including social aggregations such as mixed species flocks, can provide a more comprehensive picture of the drivers of change in tropical avian communities. The lowland tropical forests of West and Central Africa are among the most understudied globally, and major gaps exist in our understanding for how resident birds is the Congo Basin and Upper and Lower Guinea forests respond to changing forest landscapes. In collaboration with Biodiversity Initiative, our research aims to unpack the relationship between species, their functional traits, behaviours and sociality, and the structural characteristics of forests they occupy. From this, we can better understand what is driving local species extirpation, or population shifts following habitat change or loss, and how this may extend to larger population trends in the region. |

Paramo and Cloud Forest, Colombia

| Bird

communities above treeline: Paramo in the Eastern

Andes of Colombia Paramos

are high elevation ecosystems above forest

treeline, occurring at elevations of c. 2800–4300

m above sea level. These areas are discontinuously

distributed in isolated mountaintops, forming an

archipelago-like distribution that exhibits harsh

abiotic conditions, such as drastic daily changes

in temperature, high ultraviolet radiation and low

oxygen pressure. Bird communities restricted to

the Paramo are highly vulnerable to the combined

effects of local fragmentation and shifting

abiotic and biotic conditions with climate change.

Our ability to predict the responses of tropical high elevation species to global changes in climate and land use depends on detailed knowledge of the life histories and behavioral adaptations that allow them to tolerate extreme environmental conditions. In the paramos of Colombia, we use field experiments, observations and comparative analysis to study the life history traits and breeding strategies of tropical high-elevation specialists, as well as the role of species interactions in determining the elevational range limits of tropical birds. |

Black Flowerpiercers

(Diglossa humeralis) and Scarlet-belled

Mountain-Tanagers (Anisognathus igniventris) are

common species that nest in paramo habitats of

Colombia. Like other high-elevation tanagers in

the Andes, this Anisognathus species has a clutch

size of only one egg.

|

Top

Back to Home