Andes Tilaran mountains Amazon

Back to Home

|

Avian diversity

in the Peruvian Andes

A

primary goal in our research is to understand spatial

patterns of species diversity in the tropical Andes.

Within the Manu Biosphere Reserve, we use

audio-visual counts and mist nets to survey birds along a 3000-m

elevational

gradient, ranging from the Amazon basin to treeline (400-3400m). We use

these data to quantify avian richness and species turnover, and to

assess how landscape heterogeneity, generated by topography and

landslide disturbance, contributes to regional diversity.

These data serve in other projects, for example, as training and

test data for species distribution models, including those that utilize

remote sensing data, for modeling species' response curves with

elevation, and for comparisons of diversity patterns to other taxa. We have documented extremely high species turnover along tropical elevational gradients, with 100% change in community composition in 500 m elevation. This is twice as high as the rate of species turnover along diverse temperate mountainsides in the Eastern US (Jankowski unpubl. data). Patterns of species turnover in birds correspond to changes in tree communities, as well as structural components of vegetation. We also highlight an important role for the position of the cloud bank and gradients in moisture for predicting community composition in these regions, factors that are expected to be altered by future climate change. Jankowski, J.E., Merkord, C.L., Rios, W.F., Cabrera, K.C., Salinas R., N., Silman, M.R. (2013) The relationship of tropical bird communities to tree species composition and vegetation structure along an Andean elevational gradient. Journal of Biogeography. 40: 950-962. Scholer, M.N., Jankowski, J.E. (submitted to Ornitologia Neotropical) New and noteworthy distributional records for birds of the Manu Biosphere Reserve. |

Cloud forest after a mid-afternoon rainstorm in Manu at 1700 m. |

Eutoxeres condamini is found in the lower elevations of Manu National Park. We might expect this species to be specialized to few flowering plant genera based on its bill morphology. Photo by Zach Peterson. | Hummingbirds and Flowering Plants in the Andes The

highest diversity of hummingbirds is found in the Andes Mountains in

South America,

where species often have elevational distributions of only a few hundred

meters. Despite well-studied specialization to flowering-plants in some species,

no one has examined how relationships between hummingbirds and

flowering plants may constrain hummingbird species’ elevational

distributions. One advantage of hummingbirds

is that they leave a record of which flowers they have visited through

accumulation of pollen on their bills and heads, thus reducing the need

for such logistically challenging studies that follow hummingbirds as

they zip through their environment. In our project, we are using the Neotropical Pollen

Database develolped by the Palynology lab of Mark Bush to help identify

pollen samples

collected from bills of captured hummingbirds along an elevational

gradient in Manu and to describe the dietery composition for 38 species of tropical hummingbirds. Combined with data on the

occurrence of those hummingbird and

flowering-plant species along the same gradient, we can address many

questions: Do range limits in hummingbirds coincide with limits in the

distribution of

their flowering plants? Do hummingbirds with broad distributions

change their use of flowering-plant resources with elevation? Are

specialist hummingbirds constrained to narrower elevational

ranges compared to generalists? My students are working on other cool

questions, with species like Sicklebills (photo left) and the evolution

of curvature in flower corollas, or territoriality and spatial use by

high elevation hummingbirds like the Shining Sunbeam.

Pavan, L., Hazlehurst, J., Jankowski, J.E. (in prep for Journal of Field Ornithology) Patterns of territorial space utilization in a tropical montane hummingbird (Aglaeactis cupripennis) Cespedes, L., Pavan, L., Hazlehurst, J., Jankowski, J.E. (in prep for Wilson Journal of Ornithology) The behavior and diet of the shining sunbeam (Trochilidae): A territorial, high elevation hummingbird. |

To

collect pollen we rub a small slice of prepared gelatin over the

hummingbird's bill and forehead. This gelatin is then melted and fixed

on a microscope slide under a glass coverslip. Photo of Ocreatus

underwoodi by Zach Peterson.

|

|

Andean

bird-vegetation associations: using

remotely

sensed data for distribution

modeling

and biodiversity mapping

The study of biodiversity in tropical montane forests has long been plagued by an inability to access and sufficiently sample the heterogeneity of these complex landscapes. Birds are among the most well studied taxa, yet even the most detailed studies of avian distributions in tropical mountains describe elevational ranges by limits of occurrence along single transects, or estimated abundance based on limited spatial sampling. For birds, we know that vegetation structure and complexity is an important predictor of species richness and is used in habitat selection for individual species, but ground-based vegetation sampling is time-consuming, spatially limited, and sometimes down right dangerous in steep mountainous terrain. Advances in active remote sensing now allow detailed, quantitative measures of vegetation to be gathered over thousands of square kilometers. This could be enormously useful for understanding patterns of avian diversity and distributions. This project will combine our data of tropical bird abundances along the elevational gradient in Manu with interferometric Synthetic Aperture Radar (inSAR) data for the entire study area. Using variables derived from radar data as indicators of vegetation structure (e.g., canopy height, above-ground biomass), we can generate landscape-scale predictions for bird species richness, variation in species composition (beta diversity), and individual species’ distributions for this Andean landscape, including population size estimates for the best modeled species. Remote sensing and GIS applications will be used to construct maps of spatial patterns of avian diversity for the montane regions of Manu National Park. |

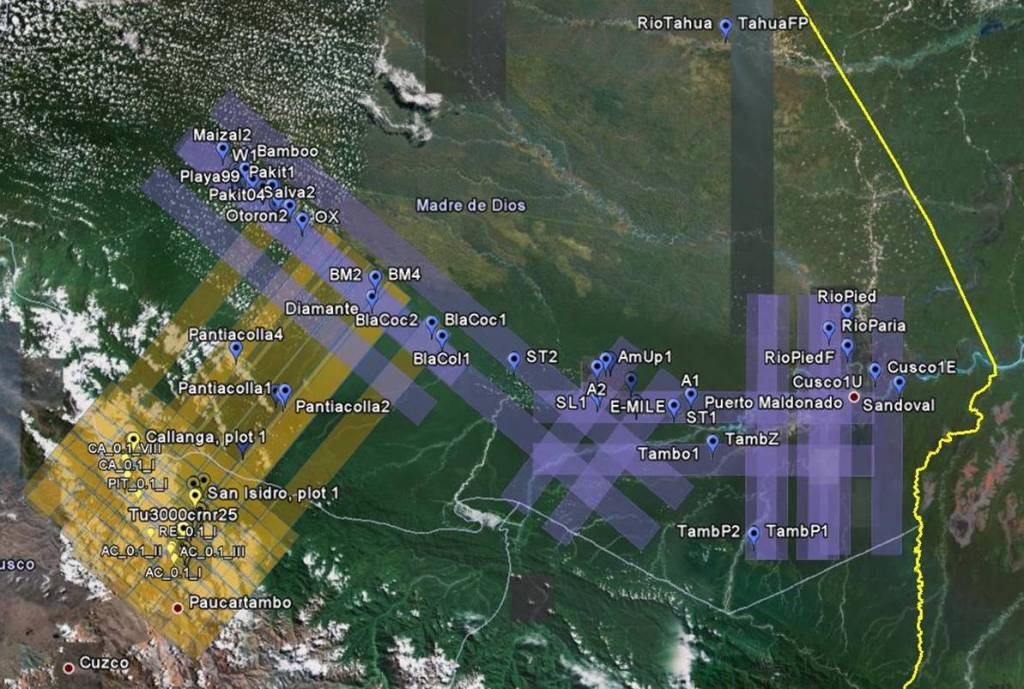

Overview of Departments of Cusco and Madre de Dios, Peru. Yellow and blue swaths indicate flight paths for remotely sensed radar data. The yellow swaths, collected in July 2009 by Earth Data, Inc., cover the montane portion of the Manu region. |

| Understanding

evolutionary relationships of Andean

birds through ectoparasitic chewing lice An

assortment of ectoparasites live on birds, among which are chewing lice

specialized to the wing feathers and body. These parasites often

track the evolutionary histories of their hosts, though this occurs in

differing degrees of cospeciation. Such relationships give us the

opportunity to study microevolutionary processes in bird hosts at regional spatial scales, such as dispersal, gene flow, and

population divergence, as well as macroevolutionary patterns

of host-parasite coevolution in species groups distributed across

biogeographic provinces. As part of

our research efforts in Manu, we have collected ectoparasites from

captured birds using a feather dusting technique. With these

data, we are joining forces with bird lice experts and collections

in the Field Museum of Chicago to investigate micro- and

macroevolutionary patterns in Amazonian and Andean birds.

Soto Patiño, J. Londoño, G.A., Johnson, K.P., Wechstein, J.W., Avendaño, J.E., Jankowski, J.E., Catanach, T.A., Sweet, A.D., Allen, J. (submitted to Biodiversity Data Journal) Composition and distribution of lice (Insecta: Phthiraptera) on Colombian and Peruvian birds: New data on louse-host associations in the Neotropics. |

This

Crowned Chat-Tyrant (Ochthoeca spodionota) was feeding nestlings near

treeline at 3400 meters. Perhaps due to this constraint, she didn't

have time to preen feathers, leaving them susceptible to chewing lice.

The barbs on her chest contour feathers have been completely

eaten, leaving only the rachii.

|

Top

Cloud

forest habitats are moisture-saturated, resulting in moss-laden tree

trunks and unmatched epiphyte diversity and abundance. Our study

shows that range boundaries of numerous bird species coincide with the

lower limit of cloud forest along the steep biophysical gradients of

the Pacific slope.

|

Endemism,

beta-diversity, and consequences of

climate change in Central American cloud forests

Collaborators: Anna Ciecka, Matthew Gasner, William Haber, Keiller Kyle, Robert Lawton, Kerry Rabenold The leeward Pacific slope of the Tilaran Mountains offers a unique opportunity to examine the effect of steep biophysical gradients on the organization of biodiversity. A central feature of this gradient is the "cloud forest margin" which is characterized by major shifts in vegetation structure and punctuated species turnover. This mountain range also exhibits extraordinarily high levels of endemism, harboring numerous species limited to Central America and an even greater proportion of species limited to the Costa Rican - Panamanian highlands. The combination of climate warming and regional deforestation are expected to generate serious warming and drying effects on the cloud forests of this region, adding to the need for urgent and precisely placed conservation efforts. Our research of the bird and tree communities of this landscape spans a decade, in which time we have quantified the diversity of avian and tree communities and the correlative effects of temperature and moisture on species composition along the gradient. We have found that many narrowly endemic birds tend to be numerically rare, in addition to being habitat specialists, creating a "syndrome of rarity" for many cloud forest inhabitants. Our yearly censusing of the bird community now allows us to assess yearly variation in abundances of cloud forest species and to provide critical data for analysis of population viability for endemic species. Gasner, M.R., Jankowski, J.E., Ciecka, A.L., Kyle, K.O., Rabenold, K.N. (2010) Projecting impacts of climate change on Neotropical montane forests. Biological Conservation 143: 1250-1258. Jankowski, J. E., Ciecka, A.L, Meyer, N.Y., Rabenold, K.N. (2009) Beta diversity along environmental gradients: Implications of habitat specialization in tropical montane landscapes. Journal of Animal Ecology 78: 315-327. Jankowski, J.E. & Rabenold, K.N. (2007) Endemism and local rarity in birds of Neotropical montane rainforest. Biological Conservation 138: 453-463. |

This Gray-breasted Wood-Wren (Henicorhina leucophrys) replaces the White-breasted Wood-Wren (H. leucosticta) in the Tilaran mountains of Costa Rica. Photo by Rosalbina Butron. |

Elevational

species

replacements: Testing the

Interspecific Competition

Hypothesis in Neotropical Birds

The phenomenon of elevational replacements between closely related species is well documented in tropical birds, especially in the Neotropics. It is assumed that interspecific competitive interactions underlie these replacements, preventing the coexistence of strong competitors. In his study of the Vilcabamba elevational gradient, Terborgh (1975) concluded that such competitive interactions could limit the elevational ranges for up to 30% of the montane species detected. These conclusions were based primarily on distribution patterns of congeners along single gradients, as well as evidence for range expansion along mountain slopes where one species of the congener pair was absent. Until now, experimental evidence to support the interspecific competition hypothesis in tropical mountains has been lacking. My project used interspecific playback experiments to test for territorial behaviors between species in their contact areas along elevational gradients. Such aggressive territorial interactions between species, if detected, would support the hypothesis that interspecific competition maintains these range boundaries in montane species exhibiting elevational replacements. Using recorded songs of target species, I conducted a series of these playbacks (control, congener, and conspecific) to birds holding territories in replacement zones between congeners, and at increasing distances moving away from these zones, where interspecific encounter rates decline precipitously. I have conducted these playback experiments in both the Tilaran Mountains, Costa Rica, and in Manu National Park, Peru. Results from the Tilaran mountains of Costa Rica show that species respond aggressively to congener songs in playback experiments where species come into contact along the gradient. As one moves away from the replacement zone, however, responses to congener songs grow weaker, and at distances well within the elevational ranges of these species, responses to congener songs cannot be distinguished from responses to negative control playbacks. While species tested in Costa Rica showed aggressive interactions with congeners at range boundaries, the strength of interspecific aggression varied between species and among genera, suggesting that some species could be behaviorally dominant. We emphasize that interspecific aggressive interactions at range boundaries, and especially asymmetries in interactions could pose constraints on species as they attempt to shift along with changing regional climate regimes. Jankowski, J.E., Touchton, J.M., Graham, C.H., Robinson, S.K., Parra, J.L., Seddon, N., Tobias, J.A. (2012) The role of competition in structuring tropical bird communities. Ornitología Neotropical. 23: 115-124. Jankowski, J.E., Robinson, S.K., Levey, D.J. (2010) Squeezed at the top: Interspecific aggression may constrain elevational ranges in tropical birds. Ecology 91: 1877-1884. (Cover Article) |

Top

| Using phylogenetic approaches to

understand suboscine diversity and diversification in

heterogeneous

Amazon forests Collaborators: Julie Allen, Jessica Oswald, Judit Ungvari-Martin, J. Gordon Burleigh |

Top

| Resilience

of

spruce-fir bird communities to invasion of the exotic Balsam Woolly

Adelgid Collaborators: Anna Ciecka, Kerry Rabenold |

Top

A

nesting Northern Mockingbird (Mimus polyglottos) attacking a "repeat

offender" threatening its nest. Photo by Aaron Spalding.

|

Mockingbirds

quickly learn to recognize individual humans

Participants: Monique Hiersoux, Doug Levey, Gustavo Londono, John Poulsen, Scott Robinson, Christine Stracey, Judit Ungvari-Martin After working with Northern Mockingbirds for several months, my lab mates, Gustavo Londono and Christine Stracey, began to talk about their mockingbirds becoming more and more aggressive toward them, as they returned periodically to monitor the nests they found. What's more is they were not acting more aggressively toward other passersby--this seemed to be directed at them. One day, Gustavo happened to walk by a nest he was monitoring on campus, when one of the mockingbirds picked him out of a crowd of ordinary college students on the sidewalk and dive-bombed at his head, to the shock of the many bystanders! These observations spurred our graduate and undergraduate research groups in the Robinson and Levey labs to organize a formal investigation of mockingbirds' ability to recognize us as individual humans. Our study, published last year in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA, received nationwide press coverage. The take home message is that mockingbirds have a spectacular ability to remember threats to their nests, much more than we have given them credit for! Check out this example of recognition ability by mockingbirds, and see if you can tell which person is the most threatening to this pair of birds! And here are links to articles in the press that covered our study: ScienceNOW, Telegraph.co.uk, CBS News |

|

Ecological

pressures

shaping bird song characteristics

Another ongoing project focuses on the

effects of urban noise on bird song characteristics. Several

studies have now shown that birds can adapt several aspects of their

songs in order to transmit a better signal in noisy environments.

In urban areas, birds may sing louder (increasing amplitude) to

overcome increased ambient noise, sing at different times of day, or

even change the pitch (or frequency) of the songs that they sing.

It is this final characteristic that we have studied in the

Northern Mockingbird. Two undergraduate students, Puja Patel and

Michele Feole, have dedicated many hours to collecting field recordings

of singing mockingbirds in and around Gainesville, spanning noise

environments that range from bustling rush-hour traffic at major urban

intersections to quiet pastures in the countryside. So far we

have found that mockingbirds in urban areas indeed sing at a higher

pitch, adjusting the minimum frequencies of their songs to avoid

competing with the low frequency rumble of urban road noise.

Non-urban mockingbirds, by comparison, maintain their songs at

lower frequencies, which can transmit easily through a less noisy

environment. This project continues to offer multiple

layers of interesting questions because of the complicated singing

behaviors of mockingbirds to mimic birds in their environment.

Find out more on our work with mockingbird song along an

urbanization

noise gradient here.Collaborators: Michele Feole, Doug Levey, Puja Patel, Marcela Salazar, Christine Stracey |

Top

Back to Home